-

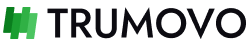

Window Wall Art Refined Canvas Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

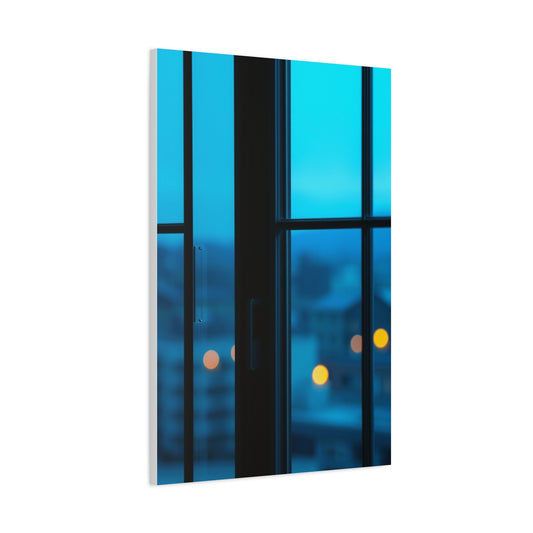

Supreme Window Wall Art Collection Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Window Wall Art Luxury Canvas Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Window Wall Art Supreme Gallery Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Supreme Window Wall Art Collection Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Vision Window Wall Art Art Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Masterpiece Window Wall Art Vision Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Elite Window Wall Art Vision Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Collection: Window Wall Art

Framed Horizons: Window Wall Art

Windows, as we understand them today, are both architectural elements and powerful metaphors. They are passages of light, boundaries between interior and exterior, and stages where countless human stories unfold. Yet, their origins were much simpler, evolving gradually from small openings in ancient dwellings to elaborate stained glass compositions and finally to the transparent panes that allowed people to gaze upon the world beyond. The earliest examples of windows were not glass at all but holes or slits in walls designed for air and rudimentary light.

These were functional rather than aesthetic, linked more to survival than contemplation. Ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia and Egypt developed early glassmaking, but this was far removed from the transparent sheets we now associate with windows. Instead, early glass was opaque, colored, or in irregular shapes, useful perhaps for jewelry or ritual objects but unsuitable for framing views. What we think of as the window in art—the frame through which one gazes outward—emerged slowly as glassmaking advanced. It was only during the Renaissance that Italian artisans began producing larger, clearer panes that transformed architecture and, with it, artistic imagination. This technical evolution gave artists new possibilities for symbolic representation. The presence of windows in paintings allowed light to filter into compositions in ways that were not only realistic but metaphorically profound. From this point forward, windows carried layered meanings: hope, illumination, aspiration, or spiritual connection.

Windows as Sacred Portals

Before the widespread use of transparent glass, the idea of the window was dominated by stained-glass traditions. In medieval cathedrals across Europe, massive windows of colored glass created dazzling spectacles of light and shadow. For a largely illiterate population, these windows became books of faith, narrating biblical stories and the lives of saints. Each pane was a page, each color a symbol, each radiance a message of divine presence. Standing within the echoing halls of a cathedral, worshippers did not merely see light—they experienced it as a spiritual medium. The role of stained glass in medieval art was not only decorative but deeply theological. The light passing through colored windows was believed to be transformed into sacred light, an embodiment of the divine touching earthly realms. Windows thus became metaphors for transcendence, acting as thresholds through which heavenly truth illuminated the mundane world. The aesthetic and spiritual power of these stained-glass works reverberated throughout the Middle Ages and shaped the symbolic role of windows in artistic thought for centuries to come. Artists who later painted windows into their works inherited this sacred resonance, even when their subject matter was secular. The sense of the window as a portal into another world—whether religious, psychological, or imaginative—was already firmly embedded in cultural consciousness.

Windows as Frames of Perception

With the Renaissance came a profound shift. Clear glass became widely available, and architecture began to incorporate larger and more luminous windows. This physical transformation of space influenced how artists depicted interiors and exteriors. The window was no longer only a glowing colored mosaic but a clear opening to the real world. Painters began using windows as compositional devices to frame landscapes, cityscapes, and skies. In portraits, windows offered contextual backdrops that suggested wealth, education, or worldly awareness. Consider Renaissance paintings of Madonna and Child where a serene landscape unfolds behind the figures through an open window. The juxtaposition of sacred figures within an interior and a natural world beyond the pane suggested harmony between divine and earthly realms. The use of windows as framing devices also reflected the period’s growing fascination with perspective. Windows provided natural vanishing points, leading the viewer’s eye outward into depth. They expanded the spatial possibilities of paintings, creating layers of reality within the canvas. Symbolically, they allowed artists to play with notions of inside and outside, public and private, spiritual and material. The act of looking out a window itself became a metaphor for knowledge, aspiration, or contemplation. It suggested the movement of the human mind outward toward discovery, curiosity, or transcendence.

Psychological Dimensions of Windows

Beyond their historical development, windows carry rich psychological associations. They are thresholds between safety and exposure, interior reflection and exterior engagement. To sit by a window is to inhabit a liminal space—neither fully inside nor entirely outside. This liminality has made windows powerful motifs in art exploring themes of longing, isolation, and identity. In portraits, figures near windows are often depicted in states of thought, dream, or melancholy. The glass pane becomes a mirror of their inner world, projecting mood onto the view beyond. For instance, Romantic painters frequently positioned solitary figures near windows to emphasize their emotional depth. The window became a conduit for longing, symbolizing unattainable freedom or distant desires. Conversely, windows could also represent intrusion. Looking in from outside suggests voyeurism or exposure, a reminder of vulnerability. Artists have used this perspective to explore themes of surveillance, curiosity, and even violation of privacy. By shifting the vantage point—inside looking out, outside looking in, or both—artworks play with the dynamics of perception and identity. A window is never neutral; it is a stage where psychological dramas unfold.

Windows as Artistic Metaphor

Throughout history, artists have embraced windows as metaphors. They symbolize clarity, vision, and insight, but also boundaries, separations, and distortions. A window can be transparent or opaque, open or closed, inviting or forbidding. Each artistic choice conveys a different layer of meaning. In surrealist art, for example, windows often blur the boundary between dream and reality. A window might open onto fantastical landscapes or impossible geometries, suggesting the permeability of the subconscious. In modernist abstraction, windows become geometric forms, reduced to planes of color or light, symbolizing perception itself. For others, windows symbolize temporality. They frame passing hours through the shifting of light, sunrise to sunset. They suggest the impermanence of experience, the fleetingness of glimpses. In this sense, windows in art embody the essence of vision—momentary, framed, mediated, and subjective. They remind us that to see is not simply to observe but to interpret, to frame, to impose meaning on what lies beyond the pane.

The Dual Gaze of Windows

One of the most compelling qualities of windows in art is their duality. They allow us to look out, but they also invite others to look in. This reciprocity complicates the act of viewing, raising questions about perspective, power, and vulnerability. When we gaze out a window, we project ourselves into the world beyond. When we imagine others gazing in, we confront the reality of exposure. This duality resonates strongly in times of social confinement or isolation. During moments of collective restriction, such as pandemics, windows take on heightened significance. They are the points through which we connect with the outside world while remaining enclosed within private spaces. In art, this duality is captured by depictions of neighbors seen across the street, lovers observed through panes, or solitary figures framed by window light. The act of seeing and being seen is interwoven, reminding us of the permeability of our private worlds. Windows in this sense are not only architectural but deeply human, shaping the very fabric of social and psychological interaction.

Windows in Renaissance and Early Modern Painting

The Renaissance provided fertile ground for the symbolic and aesthetic development of windows in art. With the rediscovery of perspective and a renewed interest in the harmony between humanity and nature, painters used windows not merely as architectural details but as devices to frame vision and invite contemplation. Artists like Lorenzo di Credi and Pinturicchio integrated windows into their compositions of sacred figures, especially depictions of the Madonna and Child. Through these openings, landscapes unfurled in soft light, creating a balance between the intimacy of the religious subject and the grandeur of the world beyond. The window thus bridged earthly and divine realms, reminding viewers that the sacred was not removed from daily life but infused within it.

By the seventeenth century, painters like Frans van Mieris and Johannes Vermeer used windows to direct light with astonishing precision. Vermeer in particular developed a signature style where a window on the left side of the composition admitted a soft illumination that bathed figures and objects in quiet brilliance. These windows were often partially unseen, implied by the light they cast rather than directly represented. Their presence, however, defined the mood of the entire painting. In works like The Astronomer or Officer and Girl, the window does more than brighten a room; it acts as a metaphor for knowledge, curiosity, and encounter. The careful rendering of light filtering through glass reflects both the technical mastery of the artist and the philosophical concerns of the era, where vision and reason were intertwined.

Romanticism and the Window of the Soul

In the Romantic period, the window became increasingly tied to inner experience and emotion. Caspar David Friedrich, whose art is suffused with meditative solitude, painted figures standing before windows as if on the threshold of transcendence. His wife, Caroline Friedrich, appears in one such painting within the quiet setting of the artist’s Dresden studio. Here the window is not only a physical opening but a symbol of yearning, an aperture toward a world of infinite possibility. Romantic windows often conveyed longing—longing for freedom, for nature, for communion with the divine. They were less about the accuracy of perspective and more about the depth of psychological experience.

This symbolic turn revealed the power of windows as metaphors of the soul. Looking outward through glass became a stand-in for introspection, for the search for meaning beyond immediate surroundings. Artists used the motif to suggest states of dreaming, melancholy, or reflection. The interior became the mind, the window its vision, and the outside world its object of desire.

Modernist Explorations of Light and Geometry

As art moved into the modernist era, windows underwent new transformations. Painters such as Pierre Bonnard incorporated them into vivid domestic interiors, where light poured through panes to energize everyday objects. Bonnard’s use of bold color and loose brushwork turned windows into dynamic fields of luminosity. They were less static architectural features and more living participants in the rhythm of his compositions.

Other modernists, like Robert Delaunay, abstracted the window entirely. His Simultaneous Windows series used fragmented planes and color to create a kaleidoscopic view of the city. The window here was not a transparent pane but a metaphor for fractured perception in the modern age. Through his work, the concept of the window was reimagined as a visual experiment, an emblem of modern vision itself.

Marc Chagall, in contrast, used windows as portals into dreamlike narratives. Works such as Paris through the Window blend recognizable skylines with fantastical imagery. For Chagall, windows symbolized the intersection between reality and imagination, between homeland and exile, between memory and vision. His use of the motif reflects the modernist tendency to dissolve boundaries, allowing windows to become thresholds to inner as well as outer landscapes.

Narrative Windows in Contemporary Expression

In the twentieth century, artists continued to expand the symbolic range of windows. Faith Ringgold, for example, employed quilted fabric to create Street Story Quilt, a triptych filled with windows. Each window framed a vignette of African American life in Harlem, capturing the richness and struggle of the community. Unlike earlier uses of windows as distant backdrops, Ringgold’s windows are immediate and intimate. They are not viewed from afar but entered into directly, each one telling its own story.

Edward Hopper, another master of windows, often depicted urban scenes where glass panes mediated loneliness and isolation. His iconic Nighthawks shows figures in a diner, visible through large plate glass windows, bathed in fluorescent light. The transparency of the windows emphasizes their vulnerability, their exposure to the silent city outside. Hopper’s windows frequently operate as barriers that heighten the sense of alienation rather than connection. His use of glass is both literal and existential, representing the fragile separation between human beings and the world around them.

Georgia O’Keeffe, though best known for her abstractions of flowers and landscapes, also turned to windows in her work. In Door Through Window, she captured the quiet geometry of her adobe home in New Mexico. Her treatment of the subject is spare, emphasizing stillness and contemplation. For O’Keeffe, the window was a frame for solitude, a distilled form that encouraged meditative looking.

Surrealism and the Window as Dream

The surrealists embraced the window as a natural metaphor for the boundary between waking life and the subconscious. Leonora Carrington included windows in dreamlike self-portraits, where they suggested access to hidden realms of imagination. Réné Magritte’s The Human Condition famously places a painting of a landscape on an easel before a window, aligning the image perfectly with the view beyond. The result destabilizes perception, challenging viewers to question what is real and what is representation. Magritte himself explained that this was a way of showing how we experience the world: simultaneously external and internal, both seen and imagined.

For surrealists, windows were not passive structures but active thresholds. They destabilized certainty, blurring the line between illusion and reality. They became symbols of the permeability of consciousness, suggesting that the act of seeing is always mediated by imagination and memory.

The Quiet Window

Not all modern uses of windows are filled with color or complexity. Some artists employed them to create moods of stillness and simplicity. Andrew Wyeth’s Wind from the Sea captures a window open to the breeze, curtains billowing slightly, light soft against the wood frame. The scene is unadorned, yet it conveys profound intimacy. It is a moment of pause, a glimpse of natural air entering a human space, a meditation on presence.

Agnes Martin, with her abstract grids, offered yet another interpretation. Though not literal windows, her works evoke the structure of panes and frames. They suggest a kind of window into silence, into the inner meditative state. Her art encourages viewers to look not outward but inward, to dwell within the subtle rhythms of perception.

The Window as Universal Motif

Across centuries, cultures, and styles, the motif of the window recurs with striking persistence. From Renaissance perspective to surrealist experimentation, from communal quilts to minimalist abstraction, windows serve as a universal language of vision and transition. They remind us of the duality of existence—inside and outside, self and other, dream and reality. They are at once literal structures of architecture and profound metaphors of human experience.

For artists, windows offer inexhaustible possibilities. They allow light to enter and shadow to fall. They create depth and distance. They suggest openness or confinement. They serve as metaphors of vision, longing, memory, and dream. The very ordinariness of the window makes it endlessly adaptable; it is a part of everyday life, yet always charged with symbolic potential.

As viewers, we respond to windows in art because they echo our lived experience. We all know the act of looking out, of watching weather change, of seeing neighbors pass, of dreaming beyond the glass. We also know the experience of being observed, of recognizing the fragile transparency that windows impose. In art, these universal moments are magnified, inviting reflection on what it means to see, to imagine, and to be human.

The Psychological Window

Windows in art often act as mirrors of the human psyche. They are not only openings in architecture but also openings into states of mind. Artists have long understood that positioning a figure by a window evokes reflection, longing, or melancholy. The posture of the figure, the quality of light, and the view beyond become symbolic of the inner life. For example, the image of a solitary woman gazing outward has appeared in countless works across centuries. From Vermeer’s domestic interiors to Berthe Morisot’s intimate pastels, the motif recurs because it resonates with a universal human act: pausing by a window to think, to hope, or to dream.

The psychology of windows is shaped by their duality. They provide security and enclosure, but they also tempt us with the world beyond. To look outward is to acknowledge desire for what is distant or inaccessible. To remain inside is to recognize boundaries, both chosen and imposed. In this sense, windows symbolize the tension between freedom and confinement. During moments of societal crisis, such as pandemics or wars, the window takes on heightened meaning. It becomes a lifeline to the world, a reminder that beyond the glass life continues. Art that depicts windows in such contexts often captures both comfort and frustration, the mingling of hope with limitation.

Windows also evoke vulnerability. To sit within a lit room while darkness surrounds is to feel exposed to unseen eyes. This psychological reversal—being looked at rather than looking out—has been explored in artworks that emphasize voyeurism, surveillance, or intrusion. The viewer of the painting may occupy the position of the outsider, gazing in upon the intimacy of another’s private world. This creates a dynamic of power and curiosity, reminding us that windows are two-way thresholds, mediating not just vision but relationships of visibility and secrecy.

The Spiritual Window

Beyond psychology, windows carry profound spiritual symbolism. In many religious traditions, light is equated with the divine. Windows, as channels of light, naturally acquire sacred meaning. The medieval stained-glass windows of cathedrals are perhaps the most famous examples, where colored panes transformed ordinary sunlight into a glowing presence that enveloped worshippers. The effect was not simply aesthetic but theological: the light was experienced as divine radiance entering the earthly world.

In Eastern traditions, too, windows have served as metaphors for spiritual vision. In Japanese aesthetics, the shoji screen window diffuses light gently, creating a harmony between interior and exterior. This soft mediation of space reflects philosophies of impermanence and subtle beauty. The window here is not a stark division but a permeable boundary, embodying the flow of nature into human dwelling.

In art, the spiritual dimension of windows often appears through their symbolic use as portals to higher realms. Renaissance paintings of the Virgin and Child, framed by open windows onto luminous landscapes, suggest that divinity is accessible through contemplation of creation. Modern abstract artists like Agnes Martin reimagined the window as a grid of calm lines, a metaphor for meditative vision, an opening not to the physical world but to inner stillness.

The spiritual symbolism of windows extends to their role as thresholds between life and death. In some traditions, the soul was thought to depart the body through a window. Artistic depictions of open windows at twilight or dawn sometimes carry this undertone of passage, suggesting transition between earthly and eternal states. The motif of the window, then, is not only architectural but existential, a reminder of the permeability between the material and the transcendent.

Windows Across Cultures

While European traditions often dominate discussions of windows in art, other cultures offer rich perspectives. In Islamic architecture, windows take the form of intricate lattice screens, called mashrabiya, which filter light into delicate patterns. In visual culture, these windows symbolize modesty and privacy, allowing those inside to see without being seen. Artists who depict such windows often emphasize their dual function as both protective and ornamental, embodying cultural values of beauty and discretion.

In Chinese art, the moon gate and circular window are recurring motifs in gardens and paintings. These architectural forms serve as symbolic frames for viewing nature, emphasizing harmony between human spaces and the landscape. Unlike the linear perspective of European Renaissance windows, these frames highlight balance and cyclical patterns. They suggest that looking through a window is not an act of separation but of unity with natural rhythms.

In Japanese woodblock prints, windows frequently appear as part of everyday domestic scenes. They are depicted with quiet clarity, framing moments of reading, resting, or contemplating the seasons. Here, the window is integrated into the flow of life rather than dramatized. The focus is on the subtle interplay of interior and exterior, human and natural, presence and absence. This cultural approach to windows underscores their role as mediators of experience rather than as stark thresholds.

The Window as Storyteller

Art is inherently narrative, and windows often function as storytelling devices. They allow viewers to glimpse what lies beyond the main subject, hinting at broader contexts or hidden meanings. A portrait framed by a window overlooking a battlefield, a seascape, or a city skyline tells us something about the sitter’s life, identity, or aspirations. The secondary scene visible through the window often carries as much weight as the primary figure.

In modern and contemporary art, the narrative function of windows has expanded into explorations of social identity. Faith Ringgold’s quilted windows tell the stories of Harlem residents, each pane a vignette of personal and communal experience. The multiplicity of windows mirrors the multiplicity of voices, asserting that every view is a perspective, every perspective a story.

In cinema, which has drawn heavily on artistic motifs, windows are used to frame narrative tension. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window famously explored voyeurism and suspicion through the act of watching neighbors across an urban courtyard. The device of the window becomes the engine of the story itself, reminding us of the narrative power this simple structure holds. Visual art anticipates this cinematic potential, using windows as devices to expand the frame of meaning.

The Universal Appeal of Windows in Art

Why do windows hold such universal appeal in art? Perhaps it is because they echo the very act of art-making itself. A painting, after all, is a kind of window: a framed surface through which we look into another world. The rectangle of the canvas mirrors the rectangle of the windowpane, each offering a constructed view. Both require us to suspend disbelief, to imagine that what we see within the frame connects to a reality beyond.

This parallel has been explored explicitly by artists like Magritte, who played with the alignment of canvas and window, but it exists implicitly in countless works across history. To look at art is to look through a window, and to look through a window is to participate in art. The convergence of these two acts explains why windows resonate so powerfully with viewers.

Windows also embody human dualities: openness and closure, intimacy and exposure, limitation and possibility. They are simple architectural features, yet they touch upon fundamental aspects of human existence. We all know what it means to gaze outward, to be drawn beyond our confines, to imagine what lies elsewhere. We all know what it feels like to be observed through a pane, to recognize our vulnerability. This universality makes windows a motif that crosses cultural boundaries and historical periods with ease.

In times of isolation, windows remind us of connection. In moments of openness, they remind us of perspective. They are never just glass and frame but symbols of vision itself. Artists across centuries have turned to them precisely because they offer inexhaustible possibilities for meaning. Whether rendered in brilliant stained glass, in soft oil light, in abstract grids, or in quilted stories, windows continue to capture imagination as both objects and metaphors.

The Window as a Boundary Between Worlds

Throughout centuries, artists have turned to the window as a metaphorical and physical threshold that separates two realms. On one side lies the intimate, domestic, and private life, and on the other, the expansive external world filled with unknown possibilities. The presence of windows in paintings and drawings often transforms ordinary spaces into sites of transition, giving the viewer a chance to meditate on themes of separation, connection, and longing. For many creators, the act of looking out of or into a window becomes a way of negotiating the human condition, addressing questions of freedom, isolation, and belonging.

Light and Shadow as Storytellers

The depiction of windows is rarely about glass alone. It is about the light that streams through them and the shadows that gather around their edges. In Renaissance works, for instance, windows often appear as sources of divine illumination, representing both spiritual awakening and the arrival of grace. Artists like Vermeer used light entering through a window to create atmosphere and mood, guiding the eye toward objects and figures bathed in its glow. In contrast, modern painters sometimes portray windows as spaces of obscurity, with muted or filtered light suggesting melancholy, secrecy, or even confinement. Light through a window is never neutral; it always tells a story.

Domestic Intimacy and Silent Narratives

Windows within interior scenes frequently highlight domestic life. A figure standing by a window, gazing outside, invites us to imagine untold stories. Is the person waiting for someone to return, longing for freedom, or simply immersed in daydreams? Many 19th-century artists captured these silent narratives, framing women or children by windows as if to emphasize the quiet rhythm of everyday existence. The window here becomes more than architecture; it is a stage on which private dramas unfold, often without a single word spoken. The viewer, peering into these moments, becomes a participant in their emotional resonance.

Windows as Symbols of Freedom and Confinement

The paradox of the window is that it simultaneously represents access to freedom and a reminder of limitations. Looking out of a window may inspire a sense of expansion, of horizons beyond reach, yet the very presence of the pane signifies that one is still enclosed. In literature and painting alike, windows have embodied the emotional tension between desire and restriction. Romantic painters often portrayed travelers, poets, or solitary figures at windows, their longing glances directed toward distant mountains or skies, symbolizing aspirations that remain unattainable. In contrast, in depictions of prisons, hospitals, or monasteries, small and barred windows emphasize confinement, highlighting the stark limits of human freedom.

The Window as a Frame Within a Frame

Artists frequently use windows as compositional devices, creating a picture within the picture. By positioning the window as a secondary frame, they guide the viewer’s attention outward to a landscape, seascape, or cityscape beyond. This device invites a layered reading of the artwork, blending interior and exterior, reality and imagination. The technique reinforces the dual nature of windows, reminding us that what we see is always mediated, both by glass and by perspective. In many modern works, the window’s role as a frame becomes even more self-aware, turning into a commentary on the act of viewing itself.

Windows and the Passage of Time

Windows also serve as instruments for marking the passage of time. Morning light spilling across a sill can signify new beginnings, while twilight seen through a window might evoke closure or decline. Seasonal changes are also visible through windows, with budding trees symbolizing spring’s vitality, and bare branches or falling snow marking winter’s stillness. In this way, artists integrate windows into larger cycles of temporality, using them as silent witnesses to the rhythms of nature and human life. A single window can hold decades of meaning when considered as a recurrent motif in art history.

Windows in Religious and Spiritual Contexts

In sacred spaces, stained glass windows have long carried spiritual significance. These luminous surfaces transform sunlight into a kaleidoscope of colors, creating an atmosphere intended to lift the soul toward transcendence. For centuries, cathedrals used stained glass not merely as decoration but as narrative devices, illustrating biblical stories for congregations who might not be literate. Beyond Christianity, windows in temples, shrines, and mosques function as mediators between divine presence and earthly life. Artists who capture such windows in their work often aim to convey both reverence and awe, reminding viewers that these architectural openings can act as conduits to the infinite.

The Window in Modern and Abstract Art

As artistic movements shifted toward abstraction, the symbolism of windows adapted to new forms. Modernists such as Matisse and Picasso used windows to experiment with perspective, color, and form, often dissolving the distinction between inside and outside altogether. Abstract interpretations of windows reflect less on literal views and more on the concepts of openness, perception, and fragmentation. In these works, the window is no longer a simple architectural feature but a metaphor for shifting viewpoints and the instability of vision. It becomes a symbol of the subjective nature of seeing and understanding the world.

Windows as Emotional Landscapes

Beyond their physical representation, windows often serve as mirrors of the emotional states of both artists and viewers. A rain-streaked window may suggest sorrow or loss, while an open, sunlit one might evoke joy and liberation. For many artists, depicting a window is less about architecture than about psychology. The transparency of glass becomes a metaphor for vulnerability, while its fragility echoes the delicate balance of human emotions. In literature and film, windows have served similar purposes, becoming recurring motifs that anchor emotional storytelling. Painters often borrow from this broader cultural resonance, embedding layers of feeling into each pane of glass they depict.

The Universal Language of Windows

What makes windows in art so enduring is their universality. No matter the culture or time period, the experience of looking through or being seen through a window is deeply human. It transcends geography and social class, resonating with people across centuries. The universality of windows allows artists to use them as symbols of longing, hope, reflection, and transformation. They embody the dualities that define human existence: presence and absence, freedom and limitation, intimacy and distance. Because of this, the motif of the window continues to inspire creators today, finding new life in photography, digital art, and installations that explore the boundaries between real and virtual spaces.

Windows as Anchors of Human Experience

The window resonates so strongly because it is universal. Regardless of culture or era, people have always lived with openings that connect inside to outside, safety to risk, and solitude to community. Artists capture these simple yet profound experiences by turning windows into visual metaphors. The act of looking through a window becomes a stand-in for the act of seeing itself, reminding us that perception is never neutral. Every gaze carries intention, emotion, and memory. This universality allows windows to serve as anchors in art history, grounding viewers in familiar experiences even as they invite deeper philosophical reflection.

The Interplay of Inner and Outer Worlds

A recurring theme in window imagery is the delicate balance between interior and exterior. Interiors suggest safety, stability, and sometimes restriction, while exteriors evoke freedom, danger, or possibility. Artists use windows to stage encounters between these realms. A figure seated by a window often represents introspection, caught between the intimacy of the room and the vastness beyond the pane. Landscapes glimpsed through windows become projections of inner states, while interiors illuminated by exterior light gain symbolic depth. In this sense, windows dramatize the tension between the self and the world, making visible the invisible dialogue between what we feel inside and what lies beyond our reach.

Windows as Portals of Imagination

Windows are not only physical openings; they are portals of imagination. They invite the mind to wander beyond immediate surroundings, to envision possibilities hidden behind the glass. Romantic artists embraced this quality, portraying dreamers lost in reverie by a window, eyes directed toward distant horizons. Even in contemporary works, the window often represents a boundary between reality and fantasy. A pane of glass can reflect a distorted version of the world, encouraging viewers to question what is real and what is imagined. In this way, windows embody the human desire for transcendence, offering not only views but also visions.

Memory, Nostalgia, and the Window Motif

For many viewers, windows evoke powerful emotions tied to memory and nostalgia. The sight of light filtering through curtains, the image of rain sliding down glass, or the view of a familiar street from inside a home can trigger recollections of childhood, family, or lost time. Artists often tap into these associations, embedding windows in scenes that feel simultaneously personal and universal. A single painted window can evoke longing for places left behind or times that can never be reclaimed. By anchoring works in sensory details of sight, shadow, and atmosphere, artists use windows to bridge the present with the remembered, turning personal memory into shared visual experience.

Cultural Interpretations of Windows

Although the motif of the window is universal, cultural contexts shape how it is represented. In Western traditions, windows often symbolize enlightenment, perspective, and the relationship between human beings and the divine. Stained glass windows in medieval cathedrals were designed to educate and inspire awe, transforming light into sacred narratives. In contrast, in East Asian art, windows and screens are integrated with ideas of harmony, balance, and the framing of nature. Traditional paintings often depict open windows or doorways as part of a fluid relationship between human architecture and the natural world beyond. These cultural differences highlight the adaptability of the motif, showing how windows absorb local philosophies and values while still speaking to shared human concerns.

The Psychological Weight of Windows

The presence of windows in art often reflects psychological states. An open window may symbolize hope, opportunity, or liberation, while a closed or barred window might convey entrapment or despair. Artists who explore themes of loneliness, confinement, or waiting frequently use windows to amplify the emotional tension of their works. A person staring out of a window may be searching for meaning, connection, or escape. Conversely, a window looking inward can represent vulnerability, exposing the private self to the scrutiny of others. These psychological dimensions make windows powerful storytelling devices, allowing artists to convey emotion without words.

Modernity and the Fragmented View

In the modern era, the symbolism of windows expanded in response to new ways of seeing and representing the world. With the rise of photography and cinema, windows became literal and figurative lenses, framing images and directing attention. In modernist painting, windows often appear fractured, distorted, or abstracted, reflecting the fragmented nature of perception in a rapidly changing world. Artists such as Matisse used windows as structural elements, blending interior and exterior into vibrant fields of color. For others, the window became a commentary on isolation in urban life, with panes of glass symbolizing both connection and separation in modern cities. The window evolved into a mirror of modern consciousness itself—dynamic, unstable, and open to multiple interpretations.

The Window in Contemporary and Digital Art

Contemporary artists continue to explore the motif of the window, adapting it to new media and technologies. In photography, windows are often used to create layered compositions, combining reflections, transparencies, and glimpses of interior spaces. In installation art, windows may be constructed, dismantled, or projected to question boundaries between virtual and physical worlds. Digital artists use the metaphor of the window in even more direct ways, with computer screens themselves functioning as windows onto digital realities. This reimagining demonstrates the enduring power of the motif, proving that even in a virtual age, the idea of the window retains its symbolic richness.

Windows and the Act of Viewing

At its core, the window is also a metaphor for the act of viewing itself. To look through a window is to frame the world, to filter and interpret reality through a lens. Artists who depict windows invite viewers to reflect on their own position as observers. Just as figures in paintings gaze outward, so too do we gaze inward through art, questioning the nature of what we see. The window thus becomes a self-reflexive symbol, reminding us that every artistic work is itself a window—a frame that mediates between the artist’s vision and the viewer’s perception.

The Enduring Relevance of Windows in Art

Why does the window remain such a compelling motif across centuries and cultures? Perhaps because it reflects the fundamental dualities of human life: openness and closure, presence and absence, intimacy and distance. In every era, windows adapt to new contexts, yet they always preserve their core resonance as thresholds of vision. Whether bathed in divine light, etched with raindrops, or glowing from a digital screen, windows invite us to look, to imagine, and to feel. They endure because they are both ordinary and extraordinary, rooted in daily life yet capable of infinite symbolic expansion.

Conclusion:

Windows reveal the act of looking as both a physical and emotional gesture, connecting interiors and exteriors, memories and aspirations, solitude and connection. They remind us that vision is never neutral but always framed by context, perspective, and desire. In every age, artists have found in windows a way to express the ineffable: the longing for freedom, the weight of confinement, the spark of imagination, and the passage of time. To look at a window in art is to be reminded that we are always both inside and outside, always both looking out and being looked upon. Beyond the frame lies the vast expanse of human experience, and the window remains its most eloquent threshold.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.