-

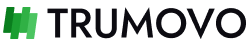

Masterpiece Vincent Van Gogh Art Vision Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

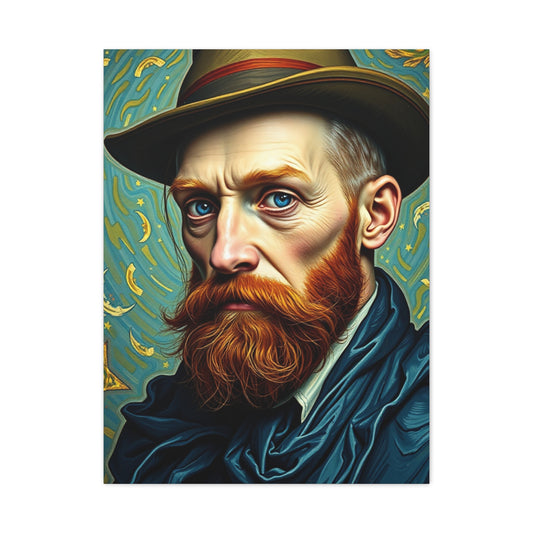

Elite Vincent Van Gogh Art Vision Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

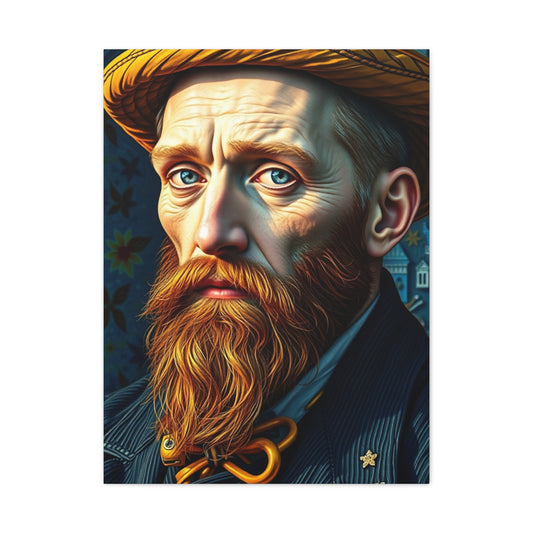

Supreme Vincent Van Gogh Art Collection Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

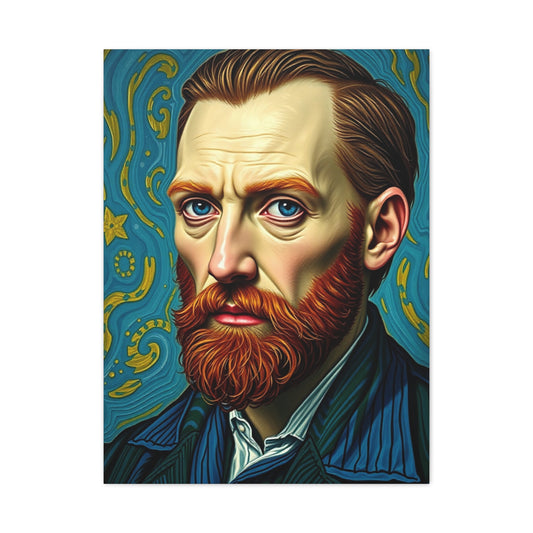

Vision Vincent Van Gogh Art Art Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Vincent Van Gogh Art Luxury Canvas Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Collection Vincent Van Gogh Art Art Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Vincent Van Gogh Art Supreme Gallery Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Vincent Van Gogh Art Refined Canvas Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Vincent Van Gogh Art Supreme Gallery Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Supreme Vincent Van Gogh Art Collection Wall Art & Canvas Print

Regular price From $141.23 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Collection: Vincent Van Gogh Wall Art

Starry Whispers: Vincent Van Gogh Wall Art

Vincent van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in the small village of Zundert in the southern Netherlands. He was the eldest of six children in a Protestant family, and his father served as a pastor. From a young age, Vincent was quiet and introspective, spending much of his time observing the natural world around him. This early immersion in nature laid the groundwork for his later artistic vision, where landscapes and natural forms would dominate his work. Vincent’s childhood was shaped by a strict moral environment, yet he displayed an innate sensitivity and curiosity that set him apart from his peers. Despite being reserved, he was deeply reflective, often contemplating the spiritual and philosophical dimensions of life.

At the age of sixteen, Vincent began working for Goupil and Co., an art dealership where his uncle was a partner. This apprenticeship took him first to The Hague, then to London and Paris, where he was exposed to a wide range of artistic styles and cultural influences. During these formative years, he developed a deep appreciation for Dutch masters such as Rembrandt and Frans Hals, as well as contemporary French painters like Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot. These artists would later influence his approach to color, composition, and the depiction of rural life. Despite his exposure to art dealing, van Gogh disliked the commercial side of the industry and felt constrained by its focus on profit rather than creativity.

Vincent’s early adult life was marked by emotional and spiritual turmoil. In 1874, he experienced a profound personal disappointment when a romantic attachment in London ended abruptly, leaving him feeling isolated and desolate. Seeking purpose, he briefly pursued a career in ministry, hoping to serve humanity through religious work. He undertook theological studies and missionary training but encountered repeated conflicts with ecclesiastical authorities, whose rigid doctrines clashed with his empathetic and compassionate worldview. His commitment to social welfare led him to the Borinage, a coal-mining region in Belgium, where he lived among the impoverished population, giving away his possessions and attempting to minister to their needs. This period of intense personal sacrifice and hardship marked the first major crisis of his life, shaping his later sensitivity to human suffering and social issues, which became central themes in his art.

During his time in the Borinage, van Gogh began drawing seriously for the first time, discovering a profound outlet for self-expression. He realized that his true vocation was not in ministry but in art, and he committed himself to the pursuit of painting as a means of bringing consolation and insight to humanity. He saw his creative mission as a form of brotherly communication, intending to depict the struggles and dignity of ordinary people. This period of self-discovery marked a turning point in his life, restoring his sense of purpose and guiding his future endeavors. Vincent’s early artistic efforts were characterized by drawings and watercolors, reflecting his keen observation of rural life and his desire to capture the essence of human experience.

Early Artistic Development and Influences

From 1880 onward, Vincent van Gogh began to devote himself entirely to art, undergoing a period of intense self-training. He studied at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts, where he developed foundational skills in drawing and composition. He spent time working in his father’s parsonage at Etten, drawing from nature and experimenting with techniques that would later define his style. During this period, he also sought the mentorship of established artists, most notably Anton Mauve, a Dutch landscape painter. Under Mauve’s guidance, van Gogh honed his ability to depict light, shadow, and texture while gaining confidence in his handling of oil paints.

Van Gogh’s exposure to literature and social commentary influenced the thematic focus of his early works. He admired the social realism of Émile Zola and sought to convey the hardships of peasant life with honesty and compassion. Works such as The Potato Eaters exemplify his commitment to portraying the dignity and struggle of rural laborers. These paintings emphasized the interplay between human suffering and resilience, reflecting van Gogh’s empathy and moral engagement with the world around him. His early landscapes, still lifes, and figure studies demonstrate a careful observation of daily life, with a focus on composition, tonal harmony, and the depiction of physical labor.

During the mid-1880s, van Gogh’s artistic journey led him to Antwerp, where he encountered the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Eugène Delacroix, and Japanese prints. The vibrancy of Rubens’s palette and the emotional intensity of Delacroix’s compositions profoundly influenced his evolving style. Van Gogh began experimenting with color as an expressive tool, understanding that hues could convey mood, emotion, and symbolic meaning. His study of Japanese art introduced him to bold outlines, flattened perspectives, and a decorative approach to composition. These influences converged in his distinctive post-impressionist style, characterized by expressive brushwork, vivid coloration, and emotional intensity.

Vincent van Gogh’s time in Paris further expanded his artistic horizons. Living with his brother Theo, who provided both financial and emotional support, Vincent encountered contemporary French painters such as Camille Pissarro, Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin. The exposure to Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques encouraged him to adopt broken brushwork, lighter tonalities, and pure colors. This period of experimentation allowed van Gogh to develop a personal idiom that would later become iconic. By observing urban life, landscapes, and portraits, he cultivated a nuanced understanding of form, perspective, and light, preparing him for the prolific period of creation that would follow in Arles.

Personal Struggles and Early Career Challenges

Despite his artistic progress, van Gogh’s personal life remained tumultuous. His sensitivity, combined with intense emotional experiences, contributed to periods of isolation and mental instability. He faced repeated frustrations in his personal relationships and professional ambitions, experiencing rejection, misunderstanding, and social marginalization. The combination of unfulfilled personal desires and rigorous self-expectations created internal conflicts that both challenged and fueled his creative output.

Van Gogh’s early career was also hindered by financial dependence and a lack of formal recognition. Although he produced numerous drawings and paintings, he sold only a single work during his lifetime, relying heavily on his brother Theo for sustenance. This reliance reinforced a sense of vulnerability but also provided the security necessary to pursue his artistic vision without compromise. Van Gogh’s dedication to representing human experience authentically often set him at odds with prevailing aesthetic norms, further complicating his professional trajectory.

His early works reveal a keen social consciousness and a profound empathy for the marginalized. Paintings such as The Potato Eaters capture the harsh realities of peasant life, emphasizing the physical labor, communal bonds, and moral dignity of the subjects. Van Gogh’s brushwork during this period was deliberate and methodical, reflecting his desire to convey authenticity and emotional truth. His evolving style balanced realism with expressive intensity, laying the foundation for the dramatic use of color and dynamic forms that would define his later masterpieces.

Transition to Arles and the Formation of a Unique Style

By 1888, Vincent van Gogh sought to escape the pressures of urban life in Paris and immerse himself in nature under a brighter, more vivid sky. He moved to Arles in southern France, where he embarked on an extraordinarily productive phase of creation. The landscapes, interiors, and still lifes of Arles reflect a newfound intensity of color and compositional daring. Vincent experimented with techniques such as direct application of paint from the tube, dynamic brushstrokes, and complementary color contrasts. This approach allowed him to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere while conveying emotional resonance.

In Arles, van Gogh’s focus expanded beyond landscapes to include portraits, self-portraits, and depictions of everyday life. He painted friends, family, neighbors, and local workers, seeking to imbue each subject with vitality and character. His self-portraits during this period reveal a heightened awareness of identity, introspection, and psychological complexity. Van Gogh’s dedication to depicting life as he perceived it, combined with his expressive use of color and form, established him as a pioneering figure in post-impressionist art.

During his time in Arles, van Gogh envisioned creating a collaborative artist community known as “The Studio of the South.” He invited Paul Gauguin to join him, hoping to establish a shared environment of creativity and innovation. For two months, the two artists worked closely together, exchanging ideas and influencing each other’s approaches. However, their personalities and artistic philosophies were often in conflict, leading to increasing tension. This collaboration, though brief, was pivotal in van Gogh’s artistic development, pushing him to explore new methods and intensify his expressive style.

The Prolific Period in Arles

Vincent van Gogh’s move to Arles in February 1888 marked a pivotal moment in his artistic career. Seeking the bright light and vibrant colors of southern France, he was determined to break free from the constraints of Parisian urban life. In Arles, he found inspiration in the countryside, the architecture, and the everyday lives of the local inhabitants. This period proved extraordinarily productive, as van Gogh created some of his most iconic works, including The Yellow House, Sunflowers, and Bedroom in Arles. The vividness of the landscapes and interiors reflected his emotional state, and his brushwork became increasingly expressive, capturing movement, light, and atmosphere with unprecedented intensity.

During this period, van Gogh experimented with the direct application of oil paint, often squeezing it directly from the tube onto the canvas. This technique allowed him to achieve richer textures and more vibrant colors. He was fascinated by the interplay of complementary colors and sought to create harmony through contrasts. His palette became brighter and more varied, moving away from the darker earth tones of his earlier work. Van Gogh’s style during this period was characterized by swirling, energetic brushstrokes that conveyed a sense of immediacy and emotional intensity. His paintings were not only visual representations but also expressions of feeling, capturing the essence of his subjects with a sense of vitality and urgency.

Sunflowers and Symbolism

Among the most celebrated works produced during Van Gogh’s time in Arles were the Sunflowers series. These paintings exemplify his mastery of color and composition. Van Gogh was captivated by the natural beauty of the flowers and the way they reflected sunlight. He used thick impasto and bold yellow hues to convey energy, warmth, and optimism. Beyond their aesthetic appeal, the sunflowers held symbolic significance for Van Gogh. They represented friendship, loyalty, and the cycles of life, themes that resonated deeply with his personal experiences. The Sunflowers series also reflects his desire to create works that could decorate his envisioned “Yellow House” studio and offer a sense of joy and vitality to those who saw them.

In these paintings, Van Gogh’s use of color and texture was revolutionary. He applied pigments in thick, swirling layers, allowing the brushstrokes themselves to become a vital component of the composition. The flowers seem to vibrate with life, their forms both naturalistic and abstract. This approach demonstrated his willingness to push beyond conventional representation, using paint as a medium to convey emotion directly. The Sunflowers series remains emblematic of Van Gogh’s ability to fuse technique, color theory, and symbolic meaning into works of enduring power.

Portraits and Human Connection

During his Arles period, Van Gogh also produced a number of compelling portraits. He was fascinated by the human face and sought to capture the psychological and emotional depth of his subjects. Friends, acquaintances, and local workers became frequent subjects, including the postman Joseph Roulin and his family. These portraits reveal Van Gogh’s empathy and attentiveness to individual character. His technique emphasized expressive line, bold color, and dynamic brushwork, allowing him to convey personality and emotion in ways that went beyond mere physical likeness.

Van Gogh’s portraits from this period demonstrate his evolving understanding of color as a communicative tool. He often used contrasting or unexpected hues to highlight particular features or to evoke mood. His works are notable for their intensity and immediacy, with brushstrokes that convey the artist’s direct engagement with his subjects. Each portrait reflects Van Gogh’s belief that art should communicate something essential about the human experience, revealing both vulnerability and resilience. These paintings underscore his conviction that art is a medium through which empathy and insight can be shared.

The Yellow House and Community Aspirations

Van Gogh’s time in Arles was also shaped by his aspiration to establish an artists’ community, which he called the “Studio of the South.” He rented the Yellow House and envisioned it as a collaborative space for artists to work, share ideas, and inspire one another. He believed that by living and working together, artists could cultivate creativity and innovation. This vision, however, was short-lived. When Paul Gauguin joined him in October 1888, the two artists worked closely for two months but soon experienced significant tension. Their differing temperaments and artistic philosophies led to frequent quarrels, culminating in the infamous incident in which Van Gogh cut off part of his own ear.

Despite the personal difficulties, Van Gogh’s collaboration with Gauguin had a profound impact on his artistic development. Gauguin’s use of symbolism, flat areas of color, and decorative patterns influenced Van Gogh to further explore expressive color and compositional experimentation. Conversely, Van Gogh’s passion, intensity, and emotional approach challenged Gauguin to reconsider his own methods. The brief but intense collaboration exemplifies Van Gogh’s commitment to artistic exploration and his willingness to engage deeply with the work of his peers, even in the face of personal and psychological strain.

Mastery of Light and Color

One of the hallmarks of Van Gogh’s work during the Arles period was his mastery of light and color. Inspired by the brilliance of the southern French landscape, he sought to capture the changing effects of sunlight on fields, buildings, and interiors. His paintings of wheat fields, orchards, and townscapes demonstrate a meticulous observation of natural light, combined with a bold, expressive use of color. Van Gogh was particularly interested in complementary color contrasts, using them to create vibrancy and intensity. His brushwork, often short, energetic strokes, further enhanced the sense of movement and luminosity in his paintings.

Van Gogh’s understanding of color extended beyond visual impact; he believed that color could convey emotion and psychological depth. For instance, in The Night Café and Starry Night Over the Rhône, he used contrasting hues to evoke tension, tranquility, or wonder. These explorations reflect his desire to transcend literal representation and to communicate the internal experience of the world. By manipulating color, line, and form, Van Gogh transformed ordinary scenes into emotionally resonant visions, demonstrating a pioneering approach to modern art.

Landscapes and the Influence of Nature

The landscapes painted in Arles represent a fusion of observation and imagination. Van Gogh was deeply attuned to the rhythms of nature, often walking long distances to study fields, trees, and skies. His depictions of wheat fields, cypresses, and blooming orchards convey both the physical beauty of the landscape and a sense of movement and life. He frequently employed dynamic brushwork and swirling patterns to evoke the wind, the sway of crops, or the flow of water, infusing his paintings with vitality.

Van Gogh’s landscapes also reflect his philosophical engagement with the natural world. He saw nature as a source of spiritual renewal and emotional solace. By immersing himself in outdoor observation, he sought to capture not only the visual essence of a scene but also its emotional and symbolic resonance. The interplay of light, color, and form in these works exemplifies his innovative approach, which combined meticulous study with imaginative interpretation.

Creative Intensity and Work Ethic

During his time in Arles, Van Gogh’s productivity was extraordinary. He painted nearly every day, often completing multiple works in a single session. This intensity reflected his belief that art was a form of existential engagement, a way to confront and understand the world. His prolific output included landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, all marked by a bold use of color and expressive brushwork. Van Gogh’s relentless dedication to painting was fueled by both personal passion and a sense of urgency, as he felt compelled to convey his emotional and philosophical insights through visual means.

Van Gogh’s work ethic, however, took a toll on his mental health. He often experienced periods of extreme exhaustion, heightened emotional sensitivity, and psychological strain. These challenges were intertwined with his creative process, as the intensity of his artistic engagement both nourished and destabilized him. Despite these difficulties, Van Gogh’s time in Arles represents a remarkable period of innovation, experimentation, and artistic achievement.

Key Works of the Arles Period

Several masterpieces emerged from this period, each reflecting Van Gogh’s evolving style and emotional depth. Bedroom in Arles exemplifies his interest in perspective, composition, and color harmony, capturing the personal intimacy of his living space. The Yellow House conveys both architectural structure and the artist’s sense of community and aspiration. Sunflowers showcases his mastery of color, texture, and symbolic meaning, while Wheatfield with Crows hints at the emotional turbulence that would later intensify in his life. Collectively, these works demonstrate Van Gogh’s ability to fuse technical skill with expressive intensity, producing paintings that resonate both visually and emotionally.

The Arles period also solidified Van Gogh’s signature style, characterized by expressive brushwork, vibrant colors, and the dynamic interplay of form and emotion. His innovative approach challenged traditional conventions and laid the foundation for subsequent developments in modern art. The paintings from this period continue to captivate audiences, reflecting both the beauty of the southern French landscape and the depth of the artist’s vision.

The Saint-Rémy Asylum and Artistic Resilience

In May 1889, Vincent van Gogh admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, seeking relief from his recurring mental crises. This period marked one of the most challenging and simultaneously productive phases of his artistic life. Confined to the asylum and its grounds, Van Gogh faced both limitations and opportunities. The strict routines, medical supervision, and isolation imposed by the asylum forced him to confront his mental state, yet they also provided a space for intense observation and reflection. Despite his struggles, Van Gogh immersed himself in painting with remarkable fervor, producing some of the most celebrated works of his career.

The asylum’s surrounding environment offered abundant inspiration. Olive groves, cypress trees, wheat fields, and the Alpilles mountains became recurrent motifs in his work. Van Gogh’s artistic philosophy during this period emphasized the direct engagement with nature and the emotional resonance of color. Confined indoors for long periods, he often painted from memory or imagination, merging observation with symbolic and emotional interpretation. This approach allowed him to create compositions that were both grounded in reality and infused with his inner experiences.

Masterpieces of Saint-Rémy

One of the most iconic works produced during Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy period is The Starry Night. Painted from his room overlooking the asylum garden, the piece captures a night sky alive with swirling stars and a luminous crescent moon. The cypress trees reach upward, bridging the earth and sky, reflecting Van Gogh’s fascination with the interplay between the natural world and the human spirit. The Starry Night exemplifies his use of dynamic brushwork, contrasting colors, and rhythmic patterns to evoke movement and emotional intensity. The painting represents a synthesis of technical mastery, imaginative vision, and personal expression.

Other notable works from this period include Irises, Cypresses, and Wheatfield with Cypresses. These paintings reveal Van Gogh’s exploration of texture, color contrast, and compositional experimentation. He often applied paint thickly, using energetic strokes to convey vitality and motion. The vibrant hues and swirling forms reflect his belief in the emotional power of color and his desire to express inner experience visually. Even under the constraints of the asylum, Van Gogh’s creativity remained undiminished, producing works that resonate with vitality, spirituality, and intensity.

Mental Struggles and Artistic Expression

Van Gogh’s time in Saint-Rémy was marked by episodes of psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, and hallucinations. These struggles inevitably influenced his artistic output. The tension between confinement and creative freedom, fear and hope, despair and optimism, is evident in the intensity and mood of his paintings. Art became a form of therapy and self-expression, enabling him to process his experiences and emotions. The act of painting offered structure, focus, and purpose amidst the chaos of his mental state.

Van Gogh’s correspondence with his brother Theo provides valuable insight into this period. He frequently described his psychological challenges, the difficulties of painting while experiencing illness, and his determination to continue creating. These letters reveal a profound awareness of the interconnection between mental health and artistic production. Despite severe illness, Van Gogh remained committed to his vision, believing that his work could communicate truth, consolation, and beauty to others. His artistic resilience during this period is both remarkable and inspiring.

Technique and Innovation in the Asylum

During his confinement, Van Gogh refined and expanded his technical approach. He experimented with impasto, layering thick pigments to enhance texture and dimensionality. His brushwork became more confident and expressive, often following rhythmic patterns that imbued his subjects with motion and vitality. Van Gogh also deepened his exploration of color theory, employing bold contrasts, complementary tones, and exaggerated hues to convey emotion and mood.

His compositional strategies evolved as well. Van Gogh often employed diagonal lines, swirling forms, and curvilinear shapes to guide the viewer’s eye and create visual energy. The interplay of foreground and background, light and shadow, and complementary colors contributes to a sense of harmony and dynamism. This technical experimentation allowed Van Gogh to transcend literal representation, producing works that resonate on both visual and emotional levels. The paintings from Saint-Rémy reflect his innovative approach, blending observation, imagination, and emotional insight into a cohesive artistic language.

Nature as Inspiration and Solace

Nature played a central role in Van Gogh’s creative and psychological recovery at Saint-Rémy. The asylum grounds, with their gardens, orchards, and surrounding landscape, provided a source of constant inspiration. Olive trees, cypress groves, wheat fields, and flowering plants became subjects for detailed studies as well as expressive compositions. Van Gogh’s engagement with the natural world was both aesthetic and spiritual. He sought to capture not merely the visual appearance of his subjects but their energy, rhythm, and emotional resonance.

This approach reflects Van Gogh’s broader philosophical view of nature as a mirror of human experience. He believed that by observing and representing the natural world with empathy and intensity, he could convey universal truths and emotional depth. His landscapes from this period are characterized by movement, vitality, and a luminous palette that captures both the physical and emotional essence of the scene. Nature offered Van Gogh a sense of connection, purpose, and solace amidst the challenges of his mental health.

Self-Portraits and Personal Reflection

Van Gogh produced numerous self-portraits during his time in Saint-Rémy, reflecting both his introspection and his ongoing exploration of identity. These works reveal his psychological state, as well as his artistic development. In paintings such as Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and subsequent studies, Van Gogh used color, brushwork, and composition to convey emotion, intensity, and character. The self-portraits also served as exercises in technique, allowing him to experiment with expression, lighting, and texture.

Through these works, Van Gogh confronted the challenges of his illness while asserting his identity as an artist. The intensity of gaze, the expressive use of color, and the textured brushwork communicate not only his physical appearance but also his inner life. These self-portraits stand as a testament to his resilience and determination to continue creating art under difficult circumstances. They exemplify his belief in the transformative power of painting, both for the artist and for the viewer.

Influence of Previous Artistic Encounters

Even while isolated at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh continued to engage with the work of other artists. He studied Rembrandt, Delacroix, Millet, and Japanese prints, incorporating elements of their techniques and compositional strategies into his own work. These influences are evident in his use of color, line, and form, as well as in his thematic choices. By synthesizing the lessons of past masters with his own innovations, Van Gogh developed a unique visual language that bridged observation, emotion, and imagination.

The influence of Japanese prints is particularly notable in Van Gogh’s attention to line, pattern, and flat areas of color. This inspiration encouraged him to explore bold compositions, simplified forms, and striking contrasts, which contributed to the distinctive visual energy of his Saint-Rémy works. Similarly, his study of French and Dutch masters reinforced his understanding of color, perspective, and composition, while encouraging him to pursue his own expressive vision.

Communication Through Letters

Van Gogh’s correspondence with his brother Theo remained a vital aspect of his creative life during the Saint-Rémy period. Through these letters, he articulated his artistic intentions, described his methods, and reflected on his psychological state. The letters reveal the depth of his intellectual and emotional engagement with art, offering insight into his motivations, struggles, and aspirations. They also provide a historical record of his creative process, documenting the evolution of his technique, the challenges he faced, and his relentless pursuit of artistic expression.

Theo’s support, both emotional and financial, was crucial to Van Gogh’s ability to continue working. Their correspondence underscores the importance of personal relationships in sustaining creativity, especially during periods of mental distress. Van Gogh’s letters serve as a testament to his reflective nature, his commitment to his work, and the enduring bond between the two brothers.

Emotional and Symbolic Themes

Van Gogh’s asylum works are imbued with emotional and symbolic meaning. The swirling skies of The Starry Night, the rhythmic patterns of olive trees, and the expressive colors of flowers all convey psychological intensity and inner reflection. Van Gogh’s approach integrates observation, imagination, and personal experience, resulting in works that communicate both visual beauty and emotional depth. The themes of nature, spirituality, struggle, and resilience recur throughout these paintings, reflecting his engagement with life, mortality, and the human condition.

These works demonstrate Van Gogh’s belief in the transformative power of art. He sought to convey not merely external appearances but the emotional essence of his subjects. By doing so, he created paintings that resonate across time, speaking to universal human experiences and offering a profound sense of empathy and understanding.

Transition to Auvers-sur-Oise

In May 1890, after spending a year at the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence asylum, Vincent van Gogh left the institution seeking both new inspiration and a return to familial support. He moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, a village north of Paris, under the care of Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, a physician and amateur painter who had connections with several leading artists of the time. This relocation marked the final chapter of Van Gogh’s artistic journey, characterized by extraordinary creativity and personal turmoil. The move offered the promise of renewed engagement with the artistic community and the countryside he so cherished.

Auvers-sur-Oise presented Van Gogh with a different visual environment compared to the south of France. The village’s rolling hills, wheat fields, rivers, and rustic cottages offered a wealth of motifs for his paintings. Unlike the structured confines of the Saint-Rémy asylum, Van Gogh now had greater freedom to explore the landscape and the people of the village. His palette reflected the northern light, with cooler tones and a more subdued chromatic range compared to the vibrant hues of Provence. The new surroundings inspired a prolific output, including landscapes, portraits, and studies of rural life.

Artistic Exploration and Landscapes

During his brief stay in Auvers-sur-Oise, Van Gogh produced over seventy paintings, demonstrating a remarkable intensity and dedication to his craft. His landscapes from this period illustrate a mastery of composition, color, and brushwork, balancing observation and emotional expression. Works such as Wheatfield with Crows and Fields of Wheat display his characteristic use of thick, energetic brushstrokes, bold contrasts, and dynamic movement. The sky often dominates these compositions, filled with swirling clouds, birds, or sunlight, reflecting his continued fascination with the interplay between nature and human emotion.

Van Gogh’s landscapes are notable for their rhythmic patterns and expressive lines, which communicate both the physical reality of the scene and the artist’s internal state. The wheat fields, in particular, symbolize life, growth, and impermanence, themes that resonated deeply with Van Gogh during this period of introspection. His ability to convey movement, emotion, and energy within the natural environment represents a culmination of the technical and stylistic innovations he had developed over the previous decade.

Portraits and the Human Element

In addition to landscapes, Van Gogh devoted considerable attention to portraiture in Auvers-sur-Oise. His subjects included the local residents, peasants, and Dr. Gachet himself. Portraits such as Portrait of Dr. Gachet and studies of the Roulin family exhibit Van Gogh’s intense focus on capturing psychological depth, character, and individual expression. He used color, line, and brushwork to convey not just physical likeness but also the emotional and spiritual essence of his subjects.

Van Gogh’s approach to portraiture during this period demonstrates a synthesis of observation, empathy, and imaginative interpretation. He sought to reveal the inner lives of his subjects, often employing expressive brushstrokes, vibrant contrasts, and symbolic elements. This emphasis on emotional authenticity over literal realism underscores Van Gogh’s commitment to an art that communicates beyond mere appearance, reflecting both the struggles and resilience of the human condition.

Mental State and Creative Urgency

Despite the outward productivity of this period, Van Gogh’s mental health remained fragile. He continued to experience periods of anxiety, depression, and emotional instability. Correspondence with his brother Theo reveals both his unwavering dedication to painting and his increasing feelings of despair and isolation. Van Gogh’s creativity during these months can be seen as both a coping mechanism and an urgent expression of his inner life, a means to confront his fears, mortality, and sense of purpose.

The intensity of his output in Auvers-sur-Oise reflects a heightened sense of urgency. Van Gogh worked rapidly, often completing multiple paintings in a single day. His brushwork became increasingly vigorous, his color choices bold and sometimes turbulent, and his compositions charged with emotional energy. This intensity has been interpreted by art historians as a manifestation of both his psychological distress and his determination to communicate profound truths through his art.

Symbolism and Interpretation

The works from Van Gogh’s final months are rich in symbolism and layered meaning. The fields, skies, and figures often convey a sense of transience, mortality, and existential reflection. Paintings like Wheatfield with Crows, with its dark, foreboding sky and birds in flight, are frequently interpreted as reflecting Van Gogh’s inner turmoil and awareness of his mortality. Yet even amidst the somber elements, there is vitality, beauty, and a sense of connection to the natural and human world.

Van Gogh’s symbolic use of color, line, and form serves as a vehicle for emotional communication. His skies, for example, are rarely neutral; they reflect mood, energy, and psychological states. His fields and landscapes are imbued with rhythm and motion, suggesting cycles of life and the interconnection between humans and nature. The combination of observation and emotional interpretation allows Van Gogh to transform ordinary scenes into profound artistic statements.

Final Days and Tragic Death

Van Gogh’s life came to a tragic end on July 29, 1890. After reportedly shooting himself in a wheat field, he survived for two days before succumbing to his injury. Accounts suggest that he remained conscious during this period, reflecting on his life and work. His final words allegedly emphasized personal responsibility and autonomy, illustrating his persistent individuality even in the face of despair. The circumstances surrounding his death, while tragic, also underscore the intensity and complexity of his life and artistic journey.

Theo, Van Gogh’s devoted brother and supporter, arrived shortly after the incident, providing comfort in his final hours. Theo’s own health, already fragile, deteriorated following Vincent’s death, and he passed away six months later. The bond between the brothers was central to Vincent’s life and career, providing both emotional support and practical assistance that enabled him to pursue his art despite financial and social hardships.

Artistic Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Vincent van Gogh’s influence on modern art cannot be overstated. Despite selling only a few works during his lifetime, his posthumous reputation grew rapidly in the early 20th century. His bold use of color, innovative brushwork, and emotional intensity profoundly influenced the Fauves, German Expressionists, and later avant-garde movements. Van Gogh’s work demonstrated that art could transcend literal representation, conveying emotion, psychological depth, and spiritual resonance.

Exhibitions of Van Gogh’s work in Europe and later worldwide helped establish him as a pivotal figure in the history of art. His letters, detailing both his techniques and philosophical reflections on art, provided invaluable insight into his creative process. These documents reinforced the perception of Van Gogh as a dedicated and visionary artist, committed to the pursuit of beauty, truth, and emotional expression despite personal suffering.

Commercial Success and Cultural Impact

In the decades following his death, Van Gogh’s paintings achieved extraordinary commercial and cultural recognition. His works have commanded record-breaking prices at auction, become iconic in popular culture, and inspired countless reproductions and adaptations. From fine art exhibitions to merchandise and media, Van Gogh’s imagery has permeated global consciousness, establishing him as one of the most recognized and celebrated painters in history.

Beyond commerce, Van Gogh’s story resonates because of its human dimension. His struggles with mental illness, poverty, and social isolation, coupled with his relentless commitment to art, create a compelling narrative of perseverance, creativity, and the search for meaning. This narrative has inspired artists, writers, filmmakers, and audiences worldwide, reinforcing the enduring relevance of his work and life.

Educational Influence and Art Scholarship

Van Gogh’s techniques, use of color, and compositional strategies continue to be studied in art schools and academic programs around the world. His work exemplifies the integration of technical skill, personal expression, and psychological insight, making it a valuable case study for students and scholars. Art historians have examined his use of impasto, complementary colors, and dynamic brushwork, contributing to a deeper understanding of both his individual style and broader developments in Post-Impressionist art.

Research into Van Gogh’s life, letters, and artworks has also shed light on the relationship between creativity and mental health. Scholars have explored the psychological dimensions of his work, considering how his emotional and cognitive states influenced artistic choices. These studies offer insights not only into Van Gogh’s genius but also into the broader human experience of creativity under duress.

Posthumous Recognition

Vincent van Gogh’s recognition as a preeminent artist occurred primarily after his death, reflecting both the shifting tastes of the art world and the enduring power of his work. While he struggled to sell paintings during his lifetime, the early 20th century witnessed a surge of interest in his oeuvre, beginning in Europe and later expanding internationally. Exhibitions in Paris, Brussels, and Amsterdam gradually introduced audiences to his bold use of color, innovative brushwork, and emotional intensity. Scholars and critics began to appreciate the originality and depth of Van Gogh’s art, situating him as a leading figure in Post-Impressionism.

The letters Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo played a crucial role in understanding both his artistic philosophy and personal struggles. These letters, often deeply introspective and detailed, provided an intimate glimpse into his motivations, techniques, and worldview. They revealed his relentless dedication to art as a form of personal expression and communication. Over time, the publication of these letters amplified his reputation, humanizing the artist and inspiring admiration for his resilience and vision.

Influence on Modern Art

Van Gogh’s influence on modern art is profound and multifaceted. His innovative use of color, expressive brushwork, and ability to convey psychological depth impacted a wide array of artists and movements. The Fauves, including Henri Matisse and André Derain, drew inspiration from his bold color palette and emotive compositions. German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, were influenced by his ability to translate intense emotion onto the canvas. Van Gogh’s focus on personal vision, rather than strict adherence to realism, also inspired later avant-garde movements, emphasizing individual interpretation and emotional resonance.

Art historians note that Van Gogh’s synthesis of observation and imagination created a bridge between traditional European painting and modernist experimentation. His landscapes, portraits, and still lifes demonstrate that expressive potential exists not only in the subject matter but also in the way paint is applied, color is combined, and composition is organized. This understanding contributed to the development of techniques that would become central to Expressionism, Abstract art, and beyond.

Cultural Impact

The story of Vincent van Gogh extends far beyond the confines of galleries and museums. His life, marked by struggle, poverty, and mental illness, has become emblematic of the “tortured artist” archetype. This narrative has permeated literature, cinema, music, and visual media, reinforcing his presence in popular culture. Biographies, novels, and films recounting his life, from his early years in the Netherlands to his final days in Auvers-sur-Oise, have contributed to a global fascination with both his personality and his art.

Van Gogh’s paintings themselves have become cultural symbols. Works such as Starry Night, Sunflowers, and The Bedroom are instantly recognizable, reproduced on posters, merchandise, and digital platforms. They have inspired not only other artists but also designers, musicians, and writers seeking to capture their vibrancy and emotive power. The combination of personal narrative, technical mastery, and emotional intensity ensures that Van Gogh’s cultural presence remains vivid across generations.

The Role of Museums and Exhibitions

Institutions dedicated to Van Gogh, such as the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, have been instrumental in preserving and promoting his legacy. These museums house extensive collections of his paintings, drawings, and letters, providing a comprehensive view of his artistic evolution. Exhibitions around the world, from Europe to Asia and the Americas, have drawn millions of visitors, attesting to the universal appeal of his work.

Temporary exhibitions have also played a crucial role in reinterpreting Van Gogh’s contributions. By juxtaposing his works with those of contemporaries and successors, curators highlight his influence on later movements and offer insights into the creative dialogues that shaped modern art. The careful conservation of his works, combined with scholarly research, ensures that each exhibition not only displays the visual beauty of his paintings but also contextualizes them within historical, cultural, and psychological frameworks.

Academic Study and Scholarship

Van Gogh’s life and works have been extensively studied in academic settings, contributing to fields such as art history, psychology, and cultural studies. Scholars have examined his techniques, including impasto brushwork, complementary color usage, and dynamic composition, as well as the philosophical and emotional underpinnings of his artistic choices. Research into his letters provides insights into the creative process, offering a unique perspective on the intersection of personal struggle and artistic achievement.

Art historical scholarship also explores Van Gogh’s impact on subsequent generations. Comparisons with contemporaries such as Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Camille Pissarro reveal how Van Gogh absorbed and transformed influences from Impressionism, Japanese prints, and classical European painting. Analysis of his work highlights the ways in which Van Gogh reconciled technical mastery with emotional and symbolic content, establishing a model for expressive painting in the modern era.

Mental Health and Creativity

Van Gogh’s struggles with mental health continue to be a focal point in discussions of his life and work. Scholars, psychologists, and art historians have speculated about conditions ranging from bipolar disorder to temporal lobe epilepsy. While the exact diagnoses remain debated, the relationship between his mental state and artistic output is undeniable. His periods of intense creativity often coincided with psychological distress, suggesting a complex interplay between inner turmoil and artistic expression.

This aspect of Van Gogh’s life has contributed to broader discussions about the connection between mental health and creativity. His story challenges simplistic notions of genius or madness, highlighting the resilience, discipline, and sustained effort required to produce art of lasting significance. It also serves as a reminder of the importance of support, as seen in the pivotal role of his brother Theo, who provided both emotional encouragement and financial assistance.

Enduring Popularity and Market Influence

Van Gogh’s posthumous popularity has also reshaped the art market. His works routinely fetch record-breaking sums at auction, reflecting not only their rarity and historical significance but also their profound aesthetic impact. Paintings such as Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Irises, and Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers have become emblematic of the value attributed to modern European art. This commercial success, while occurring long after Van Gogh’s death, underscores the lasting appeal and universal resonance of his vision.

Collectors, museums, and galleries around the world continue to seek Van Gogh’s works, resulting in meticulous provenance research and advanced conservation efforts. The intersection of artistic, cultural, and economic value has made Van Gogh an enduring figure not only in the history of painting but also in the global art market.

Van Gogh in Education and Popular Media

In addition to exhibitions, Van Gogh’s life and work are widely studied in educational contexts, from primary schools to universities. His techniques are taught as part of curricula in art history, painting, and visual culture courses. Students examine his use of color, line, and composition, while also exploring the biographical context that shaped his work. Van Gogh’s letters are frequently analyzed for their literary qualities, philosophical insights, and reflections on artistic practice.

Popular media has further amplified his presence. Films, documentaries, and novels explore his struggles, relationships, and creative process. Animated and illustrated interpretations of his paintings introduce younger audiences to his distinctive style, while digital platforms and social media ensure that his influence extends to contemporary visual culture. These educational and media representations reinforce the enduring relevance of Van Gogh’s work, bridging the gap between historical scholarship and everyday appreciation.

Global Artistic Influence

Van Gogh’s impact is truly global. Artists from diverse cultural backgrounds have drawn inspiration from his expressive techniques and emotive compositions. In Asia, Africa, and the Americas, painters, illustrators, and designers reinterpret Van Gogh’s stylistic innovations in local contexts, blending traditional motifs with his approach to color, texture, and form. This cross-cultural influence highlights the universality of his vision and the adaptability of his techniques across artistic traditions.

The posthumous influence of Van Gogh extends to contemporary art movements such as Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism, and figurative painting. His emphasis on personal vision, expressive brushwork, and emotional authenticity has encouraged artists to prioritize individuality, imagination, and emotional resonance over strict adherence to representational accuracy.

Legacy of Resilience and Artistic Integrity

Ultimately, Van Gogh’s legacy is inseparable from his personal story. His resilience in the face of poverty, mental illness, and societal indifference underscores the profound dedication required to pursue a life of art. Van Gogh’s integrity as an artist—his commitment to expressing his inner vision and to exploring both technical mastery and emotional depth—serves as an enduring model for aspiring creators.

His life exemplifies the tension between suffering and creation, isolation and connection, despair and inspiration. It is this tension that gives his works such remarkable emotional power and lasting relevance. Van Gogh’s art continues to resonate because it embodies the universal human struggle to find meaning, beauty, and expression, even under the most challenging circumstances.

Conclusion:

Vincent van Gogh remains one of the most influential and recognizable figures in the history of art. His journey from obscurity and hardship to posthumous acclaim reflects the transformative potential of art to transcend personal limitations, cultural constraints, and temporal boundaries. Van Gogh’s innovation, emotional depth, and commitment to truth in painting reshaped the trajectory of modern art, influencing countless artists and movements across the globe.

His story continues to inspire not only artists but also audiences seeking to understand the interplay between life, emotion, and creativity. The intensity, originality, and humanity of Van Gogh’s work ensure that his influence endures, making him a timeless symbol of artistic passion, resilience, and innovation. In both historical and contemporary contexts, Van Gogh exemplifies the power of art to convey universal human experiences, evoke profound emotion, and leave an indelible mark on culture.

Through museums, scholarship, media, and global artistic practice, the legacy of Vincent van Gogh endures. He remains a testament to the capacity of a single individual, armed with vision, skill, and emotional honesty, to transform the way the world sees and experiences art.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.